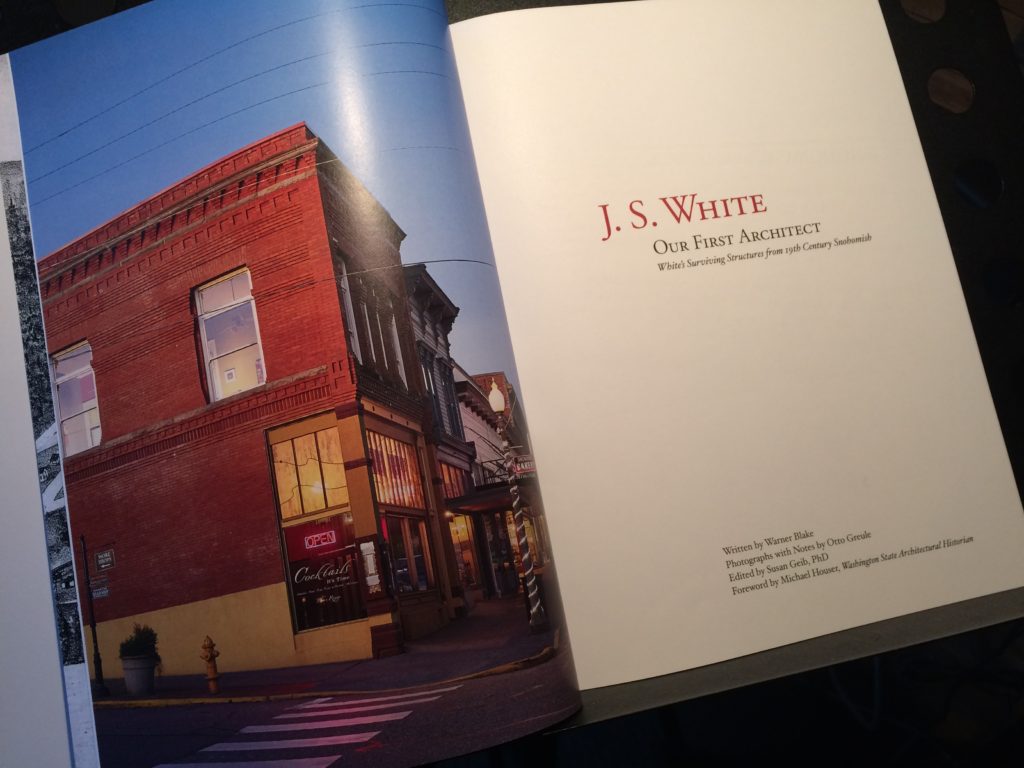

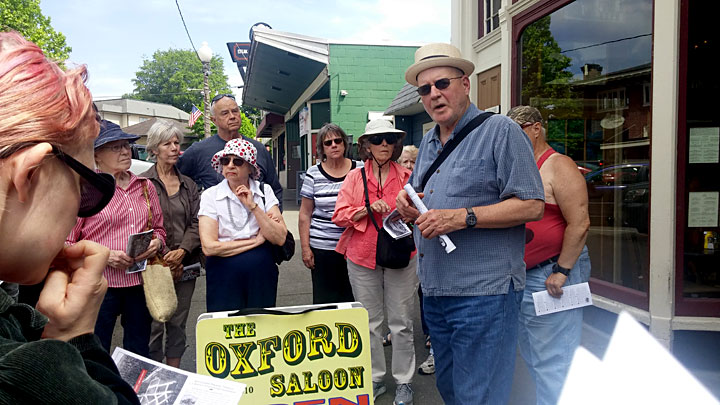

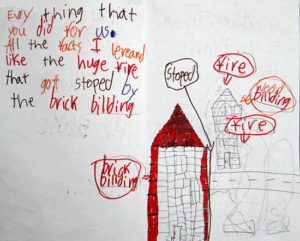

The graceful red brick building at 924 First Street was called the Princess Theater Building when I led my first walking tour of historic downtown Snohomish in 2005. Six years later I went digging for more news about the Princess Theater for a HistoryLink.org Cybertour, and came up surprisingly empty handed. Surprising because who ever heard of a theater that didn’t advertise?

The Princess Theater. This fuzzy image included on page 46 of the Snohomish Historical Society’s “River Reflections, Volume One,” published in 1975, evidently gave the building at 924 First Street its name over the years although no record has been found of the theater’s life in Snohomish; nor a better photograph.

The Princess Theater. This fuzzy image included on page 46 of the Snohomish Historical Society’s “River Reflections, Volume One,” published in 1975, evidently gave the building at 924 First Street its name over the years although no record has been found of the theater’s life in Snohomish; nor a better photograph.

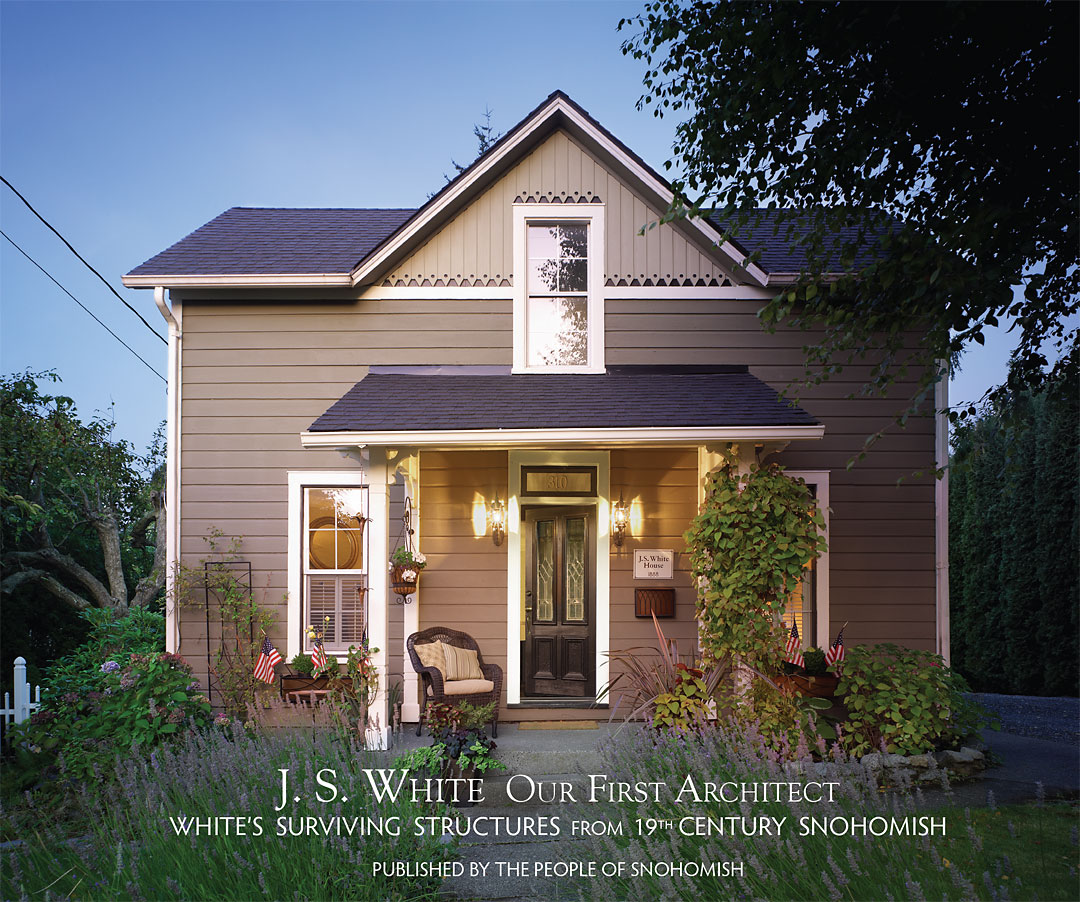

Reaching a dead-end and a deadline, I wrote what I had about the building which you can read today on the HistoryLink.org website; but do it soon, because the entry will be changed to reflect its new name, “The White Building.”

The story begins with a four line report in The Weekly Eye, December 29, 1888:

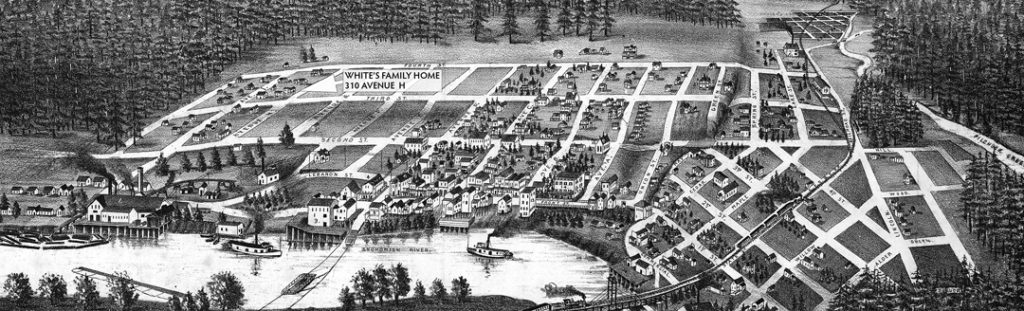

“E. C. Ferguson this week sold a portion of the lot at the corner of First and A streets, with 25 feet frontage to J.S. White, the architect and builder; for $40 a front foot.”

But no follow up and no building appears on the Sanborn Insurance maps? Three years later, in the December 22, 1892 issue, a news item jumps out announcing that White’s corner lot is being graded for a shooting gallery! The plot thickens whenever guns are involved.

Fast forward to a mention in the April 27, 1893, issue:

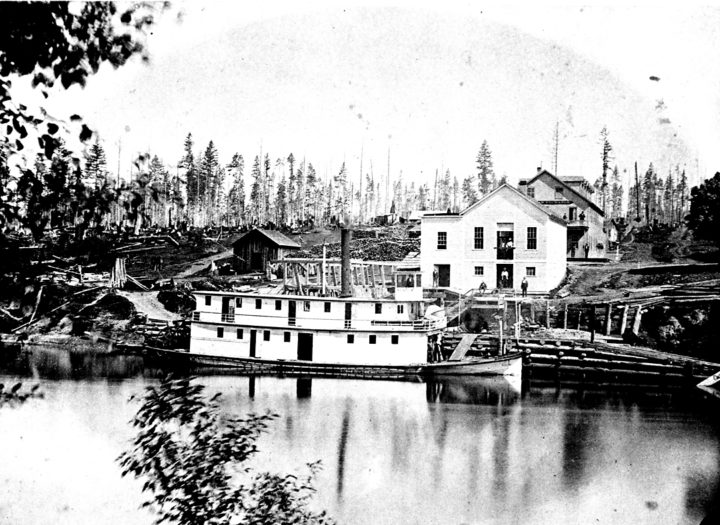

“A scowload of stone for the foundation of J. S. White’s building at First street and Avenue A has arrived from the Chuckanut quarry.”

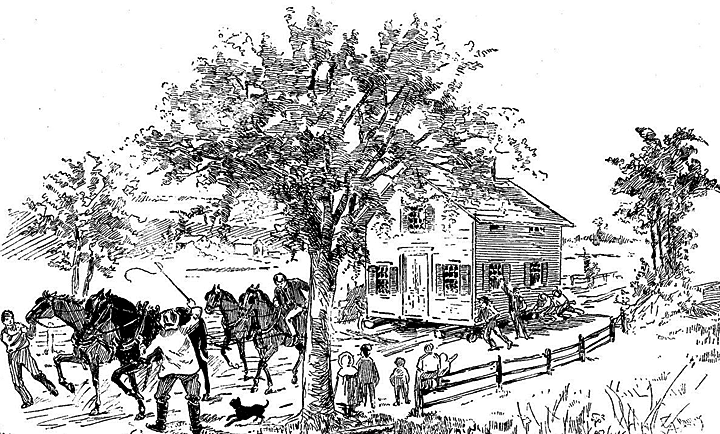

Picture a barge floating low, loaded down with stone coming upriver.

The following month, an issue over property lines was raised in the City Council Chambers by White’s attorney Hart who claimed that the Palace Saloon, next door, was four inches over its property line and asked the council to have it removed.

“The council were not convinced of their duty to do so and instructed Mr. Carothers to survey First street from D to A and fix the corners,” the report concluded. A subsequent meeting recorded the numbers without determination if the saloon was over the line.

White finished his two-story building and welcomed his first tenant, The City of Paris boutique occupying the first floor. The same issue, August 10, 1893, reported this tidbit about the odd layout of the second floor:

“People who have observed the arrangement of the rooms in the second floor of White’s new building have wondered what they were intended for. The plumbing is unusually elaborate, there are two bathrooms, a kitchen with a place for a range, a dining room, ample closets, and all necessary accommodations for housekeeping on a large scale. Yesterday Mr. White disclosed the fact that he put up the building and arranged the upper story as described at the instance of a city physician who desired to occupy it as a hospital. Mr. White added that the physician had changed his mind and that any responsible party who wants to rent a hospital is invited to call and inspect the premises.”

In a plot twist from the pages of a mystery, the new Bakeman Furniture Building, just down the street on the southeast corner of Avenue B, burns to the ground on September 15, 1893, following an unsuccessful incendiary incident in July.

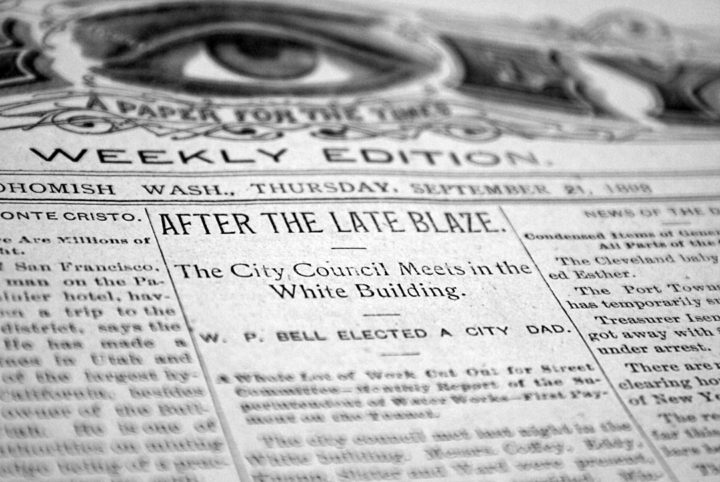

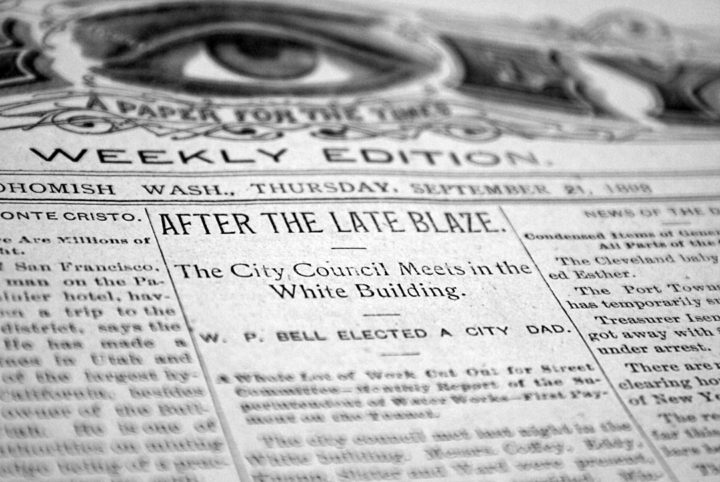

The Weekly Eye, September 21, 1893

No loss of life reported, but the city council lost its meeting place. The editor showed restraint with no mention of how fitting it was for our council members to be meeting in a hospital.

. . . .

Published in the Snohomish County Tribune, June 18, 2014