Around 1910, Ben and Nettie Morgan commissioned J.S. White to design and build a beach cabin on Whidbey Island. The story is told in the endearing memoir, “Down to Camp,” by Frances Wood, who is pictured above with the family cabin.

By 1890, it was the summer tradition among several Snohomish families to shutter their city home and board a steamship loaded down with enough supplies to last a generous part of August camping on a beach across Possession Sound. Since, for many years, the journey began by going down the Snohomish River, the annual event became known as going “down to camp,” well into the age of the automobile. At first platforms with tents were set-up on a relatively narrow shelf of land between the water and a steep bluff, then modest cabins sprouted up year after year, all in row, along a foot path still referred to as “Camper’s Row.”

By 1890, it was the summer tradition among several Snohomish families to shutter their city home and board a steamship loaded down with enough supplies to last a generous part of August camping on a beach across Possession Sound. Since, for many years, the journey began by going down the Snohomish River, the annual event became known as going “down to camp,” well into the age of the automobile. At first platforms with tents were set-up on a relatively narrow shelf of land between the water and a steep bluff, then modest cabins sprouted up year after year, all in row, along a foot path still referred to as “Camper’s Row.”

Ben and Nettie purchased a lot in 1902 and around eight years later, commissioned White to build a cabin to replace their tent, a choice perhaps based on his association with Ben’s father. They christened the structure “Camp Illahee,” a word of the indigenous people carrying “a sense of home, and connections between people and living place,” according to Frances.

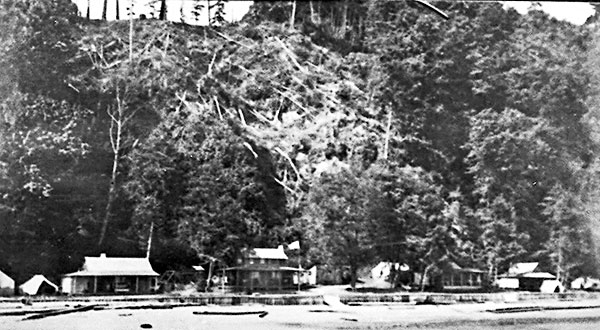

Camper’s Row on Whidbey Island, 1914, Camp Illahee is the cabin with the flag in the center, note tents to the left. The steep bank was vulnerable to land slides, as the one pictured here, and in 2015 a major slide left the historic cabin filled with mud.

Camper’s Row on Whidbey Island, 1914, Camp Illahee is the cabin with the flag in the center, note tents to the left. The steep bank was vulnerable to land slides, as the one pictured here, and in 2015 a major slide left the historic cabin filled with mud.

Three decades later, Frances tells us, her grandparents purchased Camp Illahee from Nettie, then married to a Taylor, who described the cabin in a letter: “… it could be rolled over and over and not come to pieces.” Regardless of this vivid pitch, Frances’s grandparents got the cabin for a low-ball offer of $1,100.

The cabin was renamed to “Drift Inn” by Frances’s parents when it was passed on to them. Fast forward through a childhood of summers spent at the beach cabin to the 1970s, when Frances and her sibling’s families are enjoying summer months at Drift Inn and the discussion of modifying the cabin comes up. The conversation involves three generations, including her grandmother Inez, the daughter of Nina and Charles Bakeman, who owned the furniture building that burned in 1893, sending the homeless city council members to White’s then-new building.

In a telephone conversation, Frances shared with me the family lore that White was given the commission because he was down on his luck and needed the work. She also remembers Inez advising the grandchildren, when remodeling, to not change the “lines” because it was designed by the famous Snohomish architect, J. S. White.

. . . .

This is an excerpt from my book in progress, “J.S. White: Our First Architect.“