Cast of Imaginary Characters:

Cast of Imaginary Characters:

John T. Hardwick

Missus Nightingale

Billy Bottom

Ivy Williams-Bottom

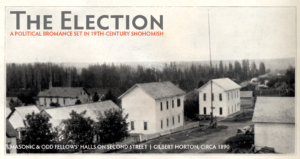

The open caucus held by the people at Odd Fellows’ Hall nominated the successful ticket, and not the convention ‘held last week’– in the saloons.

The Eye, June 28, 1890

The city manager is out, and Snohomish’s ‘strong’ mayor is in. Daily Herald, November 29, 2017

. . . .

The steamer Nellie carried a party of excursionists, numbering in all twenty-five persons to a point on Whidby island a short distance south of Holmes’ Harbor, where they have been enjoying themselves camping out, hunting, fishing, etc. The Eye, August 30, 1884.

The talk of Mayor Hardwick’s rescue, or ascension as it’s mockingly called, began while waiting for the tide to recede and take the giddy passengers downriver to camp. Steamship Nellie was filling up with the usual characters and their bulky camping gear. Their destination was a strip of beach a short distance across Possession Sound at the base of a steep bluff.

Edith Blackman, arrived in Puget Sound country with the Blackman families’ migration from Maine in 1872, as a babe in arms. (Snohomish Historical Society)

Young Edith Blackman held the rapt attention of a cluster of young women leaning in to hear her undercover eye-witness account of the action. From time to time, Edith would wear pants, which gave her access to public events without drawing attention to her gender. Following every word was Sylvia Ferguson, the first child of E. C. and Lucita; it was her father who lost the election to Reverend Hardwick. Her bright eyes seemed stuck open as she listened to Edith’s vivid telling of the newly elected, nearly naked mayor rising up in the excavation basket.

“What happened to his clothes?” she asked.

“This woman they call Missus Something-or-other removed his trousers and they were coated with mud and his leg was broken or something and she tore his shirt to make a splint – he was pushed from the sidewalk, you know,” explained Edith, pantomiming a pushing gesture and looking down. “My father told me that,” she said, looking up to see her father, Elhanan.

“Yes, our boy mayor got thrown out of the Palace Saloon for ranting in people’s faces, again! Yelling how they were all sinners and the whole lot of ‘em were going to hell!” Elhanon Blackman paused, staring into the eyes of each listener, playing the part a bit. “Finally this big guy says: How about you go to hell right now, and hits Hardwick square in the jaw, down he goes, one punch, while others drag him out onto the sidewalk.”

Mr. Blackman was on a roll: “A well juiced-up group followed the hapless Hardwick being dragged outside with their eyes on the deep, dark excavation pit for White’s foundation that was right next door to the Palace and,” pausing for maximum effect, “over the edge he went with barely a second thought or squeak from anyone. That’s when it started raining.”

Rousing cheers rose from the passengers sparked by the three sharp blasts of Nellie’s horn and she was set free. It was a bright, sunny day on the Snohomish River. It was full, bank to bank, yet very still, reflecting the blue sky and turning the tall cedars upside down in the slow current disturbed only by Nellie’s shallow wake.

Elhanan Blackman had taken over telling the story begun by his daughter. His wife, Frances, joined the group gathered at the bow of Nellie. She was tired of the story, as her daughter, Edith, told it to her over and over again, but she wanted to take in the mirror-like reflections of the water before “Nellie ran over them,” as she would say.

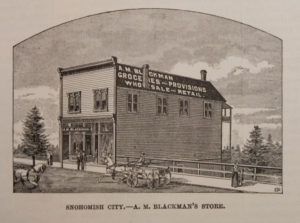

Elhanan and his brothers were lumbermen from Maine who quickly established a logging camp and mill in Snohomish and were rightly revered as the economic power of the community.

“This so-called Reverend Hardwick, with his crazy talk of some Jesus character sent here to save us, wouldn’t have gotten to first base without this Billy Bottom lowlife getting in everybody’s face,” Elhanan said. (Snohomish was a baseball town and its team, the Pacifics, was doing quite well.)

Young Jenny Durham jumped in. “He would make up a list of young women’s names in town that he accused of being witches, pagans, then post it at the Sisters of Mercy church … I, ah … I was horrified to find my name on that list,” she confessed to the group. Tears touched with rage, filled her eyes.

“Me too!” claimed Frannie Churchill, suddenly, and all turned toward her as if rehearsed.

“And me!” confessed Sylvia, Frannie’s best friend. They were about to begin their first year at the University of Washington together. “A group of us would mock his rantings on the street corner; men did too, but only women’s names are on his list.” Sylvia continued, “It’s truly troubling how many people were intimidated by his crazy thinking.”

“What happened to Hardwick and his position as mayor?” Jenny asked.

“It was fascinating!” said Blackman with a loud sigh. “Our rabid mayor returned to council meetings a changed being – he would stare into space with a faraway look and spooky smile on his face. He couldn’t or wouldn’t talk, instead kept trying to say Je-sus!”

The conversation fell silent as Nellie passed Lowell on the port side. A group on the dock watched, then waved as the sternwheeler chugged slowly on, not stopping to pick up campers this year.

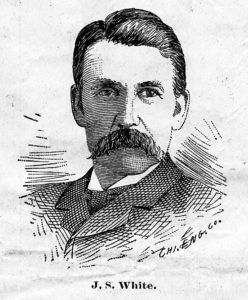

“And that Billy Bottom character, I tell you, he pestered White and the council members to the point of exhaustion until they finally passed an ordinance that prohibited shooting galleries in Snohomish just to shut him up. But White had already given up his original plan for one in the basement — that’s why the foundation pit was so deep – for headroom,” explained Blackman. “I could have told White that it was going to be tough to keep it dry because of the high water table.”

“But Bottom told anyone who would listen,” interrupted Edith, “that there will always be a puddle of water in that basement to mark the spot where his brother-in-arms, John Hardwick, fell to earth on that bright, Sunday, June morning!”

“Does anyone know what happened to this Bottom fellow?” asked Mary Low Sinclair, who was standing next to Charles Missimer, the founder of Lake Stevens. “We’ve been spared his ugliness around town for months, it seems.”

“Don’t know for sure, but heard that he and his wife moved to the brand new state of Montana … if so, good riddance!” said Blackman in a manner that brought the conversation to an end.

Shortly afterward, Nellie reached the mouth of the Snohomish River to a great cheer as she bravely entered the choppy expanse of Possession Sound, headed for Hat Island where they would stop for lunch. The wind picked up, but it was to their back, so all remained watching the horizon to the west – who would be the first to spot a tell-tale sign of their beach?

Come November there would be the regular election with the expectation that the civic life of Snohomish would return to its normal ups and downs; for now, thoughts were of sunshine, swimming, and clams — they were going down to camp.

. . . .

Follow Snohomish Stories on Facebook.

This story is inspired by the wonderful book Down to Camp: A History of Summer Folk on Whidbey Island by Frances L. Wood and available from Blue Heron Press. The featured image is from the Ferguson Album held by the Snohomish Historical Society. Postscript: To this day the basement of the White Building, 924 1st Street, is not open to the public.

. . . .

The precarious foundation of the Palace Saloon was exposed on the east side of White’s excavation. It is a two-story wooden building that was quickly built three years ago to cash in on the town’s railroad boom. Before the excavation began, White’s attorney, Mr. Hart, presented White’s claim that it encroached four inches on White’s lot to the city council. The “city dads,” as The Eye referred to the elected members — and of which J. S. White was a new member — passed the entire awkward situation on to the city engineer, Mr. Carothers, who was charged with the task: “To survey First Street from Avenues D to A and fix the corners.” Mr. Carothers’ numbers have stuck to this day.

The precarious foundation of the Palace Saloon was exposed on the east side of White’s excavation. It is a two-story wooden building that was quickly built three years ago to cash in on the town’s railroad boom. Before the excavation began, White’s attorney, Mr. Hart, presented White’s claim that it encroached four inches on White’s lot to the city council. The “city dads,” as The Eye referred to the elected members — and of which J. S. White was a new member — passed the entire awkward situation on to the city engineer, Mr. Carothers, who was charged with the task: “To survey First Street from Avenues D to A and fix the corners.” Mr. Carothers’ numbers have stuck to this day.