Cast of Imaginary Characters:

John T. Hardwick

Missus Nightingale

Billy Bottom

Ivy Williams-Bottom

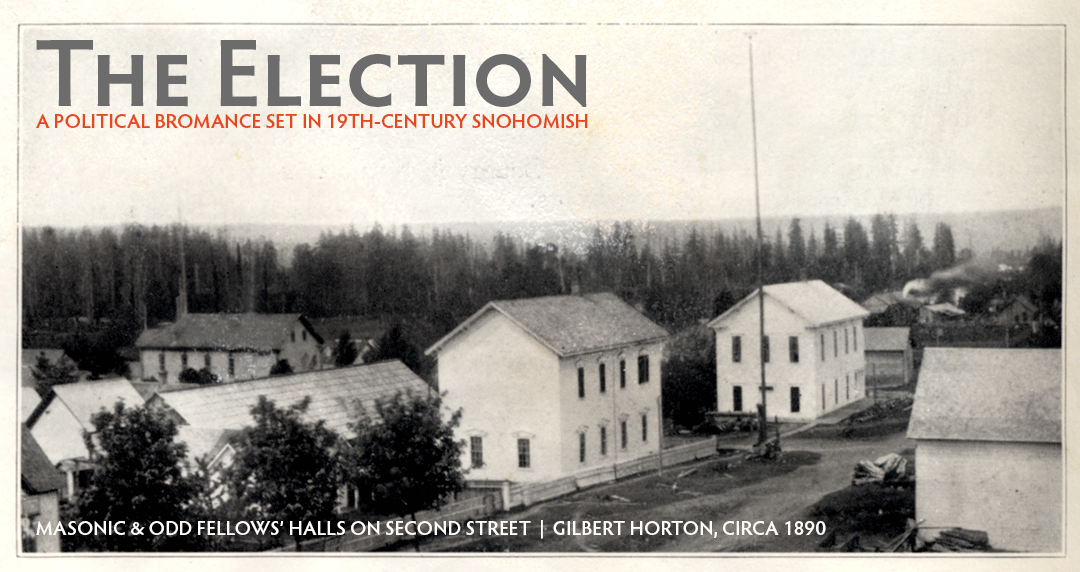

The open caucus held by the people at Odd Fellows’ Hall nominated the successful ticket, and not the convention ‘held last week’– in the saloons.

The Eye, June 28, 1890

The city manager is out, and Snohomish’s ‘strong’ mayor is in. Daily Herald, November 29, 2017

. . . .

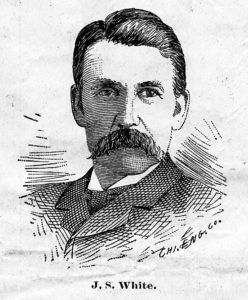

It had rained hard that night. All night long, for those with nowhere to sleep. When Rev. Hardwick’s body was discovered in first light, only his nose and toes were above water. The new mayor was lying in a substantial puddle of cocoa-colored water in the deep excavation pit for J. S. White’s new building at the corner of A and Front.

“He dead?”

Vagrants or loggers without a dime for a room were the first on the scene. An assortment of men in dark, wet wool jackets, showing no signs of urgency, were gathering behind the flimsy construction site barrier of stripped fir saplings. The excavation pit was an impressive site, a draw of attention on its own. It spanned 40 feet in width and nearly twice that in length. Starting at 10-12 feet below the wooden sidewalk, it pushed even deeper as it cut into the gentle slope of Avenue A.

“Morning Mayor!” sang out a big man wearing a top-hat and a colorful blanket of dyed goat fur over his shoulders. Unbuttoning his fly, he let go a proud stream into the pit.

Snohomish was founded on a sunny day. The picturesque town is sited on the gentle slope of the north bank of the river it was named after, which in turn was named after an Indian tribe. It’s Sunday morning; otherwise many of these boys would be in the Palace Saloon playing cards with the last of their greenbacks before heading back to their respective logging camps up the Pilchuck and French creeks.

“Nah, he ain’t dead … He was preaching again at the Palace … Jabbering on-and-on until someone hits him in the face … The only way to shut em up,” claimed the man with the large belly, struggling to button his fly.

The precarious foundation of the Palace Saloon was exposed on the east side of White’s excavation. It is a two-story wooden building that was quickly built three years ago to cash in on the town’s railroad boom. Before the excavation began, White’s attorney, Mr. Hart, presented White’s claim that it encroached four inches on White’s lot to the city council. The “city dads,” as The Eye referred to the elected members — and of which J. S. White was a new member — passed the entire awkward situation on to the city engineer, Mr. Carothers, who was charged with the task: “To survey First Street from Avenues D to A and fix the corners.” Mr. Carothers’ numbers have stuck to this day.

The precarious foundation of the Palace Saloon was exposed on the east side of White’s excavation. It is a two-story wooden building that was quickly built three years ago to cash in on the town’s railroad boom. Before the excavation began, White’s attorney, Mr. Hart, presented White’s claim that it encroached four inches on White’s lot to the city council. The “city dads,” as The Eye referred to the elected members — and of which J. S. White was a new member — passed the entire awkward situation on to the city engineer, Mr. Carothers, who was charged with the task: “To survey First Street from Avenues D to A and fix the corners.” Mr. Carothers’ numbers have stuck to this day.

During the excavation, large baskets loaded with dirt, dug by hand, were pulled to street level using a wooden block and tackle rig set in a tower, pulled up by horses, then dumped into Avenue A, eventually to be graded. Alerted to the commotion, business owners timidly climbed into the pit on a steep, rickety ladder to get a closer look at the new mayor — but they seemed more concerned about the Sunday shine on their boots. Shifting from foot to foot, they mumbled, mixing the sandy glacier till with water into a creamy, chocolate mud.

“Yup, it’s Hardwick again, son-of-a-bitch … thought he’d cut out the preaching now that he’d done won.”

“Heard this is going to be a shooting gallery,” claimed a short fellow looking around and then back to the passed-out Hardwick as if he could confirm his claim.

“Has anybody seen Ferg this morning?” Asked another looking down at his mud-covered boots.

“A what?”

“An indoor shooting range,” replied the man with the news, “read it in the paper.”

“The world’s upside down … amazing the river don’t just rain down and wash us all away!” The man had untrimmed mutton chops that made him look like a puppet talking.

“We done got a good cleaning last night,” said the small man who was wondering about Ferguson.

“In the basement? How does that work? Bullets bouncing off the walls all over the place,” asked another, waving his arms around, happy to have the topic as a diversion.

“Here comes the sun!” quietly exclaimed another with his back to the group; he had removed his bowler as if paying respect to the mysterious orb as it rose above the Palace Saloon.

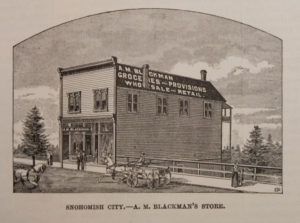

“They got ’em on the east coast, small bore rifles that use no gunpowder, I mean, I don’t know how it works … just overheard talk in the store is all,” explained the short fellow who works in Blackman’s grocery.

“They got ’em on the east coast, small bore rifles that use no gunpowder, I mean, I don’t know how it works … just overheard talk in the store is all,” explained the short fellow who works in Blackman’s grocery.

“Seems out of reach for this neck of the woods,” murmured another member of the elite group, looking for something to contribute.

“I can’t believe the dumb-shit won … what does he know about running a city? He can’t even control a horse and buggy. Saw ’em last week with a rig from Elwells, Heaven help us!” It was the puppet talking to no one in particular.

“He can learn on the job – at least he ain’t no tax-dodging moss-back like Ferg!”

The short, well-dressed fellow is referring to E. C. Ferguson, who had been mayor since he founded the town, and his loss in the election for incorporation was a dramatic upset, no doubt about it. Even the Sun, Ferguson’s paper, admitted as much under its two-word headline: “Snohomish’s Democratic.” The election divided the people between those who wanted to create a larger town and those, like Ferguson, who wanted no change. He had undeveloped lots west of Avenue D that wouldn’t be taxed if the town remained a village of the fourth-class.

In the election held on June 26, 1890, incorporation as a third-class city passed, 360 to 21 votes in a town of 2,012 souls living within the contested boundaries of the larger Snohomish City.

“Someone get word to Billy,” shouted Missus Nightingale from the top of the ladder. She started down, one-handed, as the other was holding up her extra-large skirt.

The men in the pit, all wearing dark clothes with white shirts, were standing in a loose semicircle around Hardwick so that the crowd, which had grown to wrap around the corner and up Avenue A, could look down from the behind the barrier and see the passed-out preacher. Yet, their view from above was obscured by the shadows falling across the body. As the men fidgeted about, flickers of sunlight illuminated Hardwick’s face and sparkled off the undulating puddle of muddy water, as if a message from Above; but now the group stepped back as Missus made her way to the unconscious Hardwick. She checked his pulse. She tapped his submerged shoulder — muddy water splashed across his face — as she called out his name: “John!” (She was way ahead of her time with CPR training.)

He stirs, begins to move, his belly rising as Missus reverently wipes the mud covering his huge belt buckle exposing the raised letters J-E-S-U-S. A sharp sliver of sunshine strikes the golden belt buckle. The men watching from above, who had grown into a noisy, jeering crowd, fall silent. Only faint, confused murmurs of “Jesus?” ripple through the men, like a soft, natural reverb. No one, to a man (only one woman was present), had seen such a thing in this riverside town. The fellow defending Hardwick earlier leans in for a closer look, then turns, looking at Missus Nightingale, “Where are his suspenders, Missus?”

Just like in a movie, the sharp, sudden sound of the whistle announcing the morning train to Seattle dominates this dramatic scene as Mayor J. T. Hardwick opens his eyes, in a close-up shot.

To Be Continued.

. . . .

About the title image above: The Odd Fellows Hall to the right was the place for a variety of public gatherings including debating the boundaries of incorporated Snohomish in 1890. The building to the left is the Masonic Lodge which served as the county courthouse until 1897; it was destroyed in the 1980s for scrap. Photo is by Gilbert Horton taken around the time the Odd Fellows Hall was built in 1886, and published in several publications of the time.