Cast of Imaginary Characters:

Cast of Imaginary Characters:

John T. Hardwick

Missus Nightingale

Billy Bottom

Ivy Williams-Bottom

The open caucus held by the people at Odd Fellows’ Hall nominated the successful ticket, and not the convention ‘held last week’– in the saloons.

The Eye, June 28, 1890

The city manager is out, and Snohomish’s ‘strong’ mayor is in. Daily Herald, November 29, 2017

. . . .

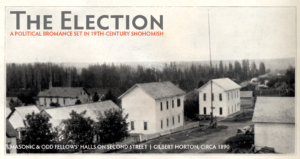

“He was a stranger!” began Preacher Hardwick in a full, rich voice which suddenly caught in his throat. He was facing a standing-room-only crowd of the Temperance Union meeting on the first floor of the Odd Fellows Hall on 2nd Street. All of the long, narrow casement windows were open, top and bottom, but no air was moving that night; it was stuck like Hardwick’s voice in the emotion of the moment.

“A stranger named Levi Bowker,” he finally continued, holding up a page from The Eye. “Did you read this?” he shouted for dramatic effect. It wasn’t necessary. The news of Levi Bowker’s suicide was the talk of the town. Hardwick made eye contact with Pherlissa Getchell sitting in the center seat of the front row. As president of the Temperance Union, it was her suggestion that he give this address — to perhaps give words to the mystery of this stranger’s death in their midst — and it sparked his political ambitions.

John T. Hardwick rarely missed an opportunity to tell people that he was born right here in Snohomish Valley, sometimes bending over and tapping the ground with the tip of his index finger. As was his father. It was his grandfather who found his way here as a circuit preacher, looking to convert Indian savages, but he met a woman and he built her a log house with his bare hands — and with hired Indian help — his wife’s brother.

Hardwick’s union produced 12 sons, who lived beyond childhood, and all were named after Christ’s Apostles. It’s not clear how many daughters lived, as they were not baptized so no records of their births exist. The dark secret of the family was that John’s father, also named John, after one of the Zebedee sons, married one of his sisters to produce a family of four sons.

Since the Hardwick homestead was remote, the arrival of a white woman into the region would have been news woven into the oral history of the family. Instead, no one talked about the dark cloud hovering over the family until it broke open with a crack of lightning, sending forth a deluge of whiskey. The memory of his father’s death haunts him; look for it in his eyes if the subject should ever come up.

John was named after John the Baptist and given the letter ‘T’ for a middle name as it was a sign of the cross. Young John was called JT while his father was alive, and it stuck. He was the youngest of the four boys and showed no interest in joining the Hardwick Bros in the growing business of installing window glass. The Seattle company was on the cutting edge of the new plate-glass window market.

JT remained on the homestead. He was close to his grandfather even though he never learned his name. He was always a formal “Grandfather” to him, something he didn’t realize until preparing words to say at the burial. Grandfather Hardwick was buried under the scrub oak tree grown from an acorn he brought from the Midwest. It grew like a weed, along with young JT, who in his sermons often embellished the story of his childhood passion for climbing that tree to see the future.

Drawn into Snohomish’s temperance movement as a young man, John T. Hardwick was handsome and easy going. His square jaw was balanced with a carefully trimmed mustache and topped by lively, dark eyes. He was quick to smile, which men were quick to mock, but the members of the temperance movement loved him. They would often meet at Joe Getchell’s two-story home on 2nd Street, next door to the Knapp and Hinkley Livery. JT was one of the few men invited to join them.

Pherlissa Getchell was a natural leader. Childless since her marriage to Joe in 1874, the daughter of a Maine farming family, and only one of a dozen white women living in the Valley at the time, Pherlissa made civilizing the frontier town where she landed her life mission. Levi Bowker’s suicide hit her hard.

Getchell House, 2nd and Avenue C, undated photograph from a glass plate negative, partial view of the livery on the right; courtesy Snohomish Historical Society.

Getchell House, 2nd and Avenue C, undated photograph from a glass plate negative, partial view of the livery on the right; courtesy Snohomish Historical Society.

It seems Bowker had a summer job on a hops ranch east of town and had been in Snohomish for about a week – two weeks before the special election of incorporation. He retired to his room in the Exchange Hotel between 9 and 10 Tuesday evening,“considerably under the influence of free campaign whiskey,” said JT, reading from The Eye.

“The hotel clerk found him the next morning, lying in a natural and easy position on the bed with his clothes on. A nearly empty morphine bottle and three brief, poorly written notes were found on the bedside table.” JT let the newspaper float to the floor while he paused to loudly blow his nose.

“One of the notes was addressed to an E. N. Porter, Port Ludlow,” he began again, “with the instructions: ‘Give my shotgun to my boy Harry if he ever comes to the Sound.’”

He held up a small piece of paper between the tips of his thumb and index finger, as if it were contagious. “Written on the back of this poll tax receipt,” Hardwick explained, then turned the hand holding the note to show the backside to his audience who, of course, were leaning in to read the message.

“For your kindness to me, keep my things. I will soon know the great mystery.” The Preacher returned the note to the lectern, looking down and repeating softly, “I will soon know the great mystery.”

Slowly looking up to speak, he added, “The third note was impossible to read, something to the effect that he was tired of life … but we know, don’t we? Yes! It was the influence of the free whiskey that made Jesus a stranger to young Levi — he chose a false savior!”

All sorts of “Amens!” filled the Odd Fellows Hall that night, overflowing through the wide-open windows.

“Only 38 years old, and a native of Springfield, Maine,” said the newspaper. “Let us pray for this stranger’s soul who will never see Jesus, but will wander for eternity.”

. . . .

“Amen!” said Missus Nightingale, holding Hardwick’s hands. He had been placed in the excavation basket used for hauling dirt out of the pit. It was a scene of eerie silence. Missus Nightingale had removed his wet, muddy clothes and boots and had set his broken leg with improvised splints. She was trying to keep his naked torso covered with his blousy white shirt.

She had washed his face, cleaned the dried blood caked in his overgrown mustache from a bloody nose, and slicked back his long black hair with her hands. The men quietly watching from above, like birds on a wire, were trying to hear what she was saying to him, but could only hear her “Amens!”

Modern ears accustomed to internal combustion engines don’t know the silence of 19th-century Snohomish. Coming from the east end of town was the rhythmic sound of horse hooves … no, a mule pulling a buckboard on the wooden planks of First Street. Its squeaking wheels announced: Billy Bottom was in town.

To be continued

. . . .